Seabird Surveys Across the Pacific with SPREP Scientists

Complementing NA166’s extensive seafloor mapping operations, this expedition includes topside surveys on the diversity and abundance of seabirds and other surface marine megafauna an activity in support of biodiversity surveys by the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). Gaining a better understanding of how seabirds, including migratory seabird species that use this open ocean pathway, will help all nations inform their conservation actions since oceans have no boundaries.

Of approximately the 11,000 species of birds worldwide, only 370 are ‘seabirds’ that spend most of their lives at sea. Of those, 42 are known to breed within Oceania, with 17 unique to our region. Other species breeding outside the region will also pass through the areas that the expedition will cover.

In addition to seabirds, the team are logging cetaceans (whales and dolphins), big fish (like marlin and sharks), manta rays, turtles, and fish schools (tuna species) encountered. Also, logged is the occurrence of marine debris as well as anything else of interest such as fishing vessels, container ships, etc.

Follow along with SPREP’s Threatened and Migratory Species Advisor Karen Baird and Chris Gaskin (Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust) in this ongoing blog!

28 [29] September 2024: Grey Noddy

Leaving Pago Pago was with great excitement for the journey ahead. Many people were on deck in what was to become the ‘Bird deck’ watching as we exited the harbor with its dramatic backdrop of Rainmaker Mountain or Mt Piao. Great Frigatebirds escorted us out of the harbour.

Straight away, we started seeing small feeding flocks of ‘tuna birds, ’ a mix of noddies, terns, and boobies. One very graceful member of this group is the Grey Noddy or Grey Ternlet. A small pale grey/white noddy which is usually only seen in inshore waters such as those we passed through around American Samoa. This one occurs in temperate as well as tropical Oceania, one we are familiar with in northern NZ, although in bird speak a different subspecies. They seem especially dainty as they hover and dip over fish schools picking up tiny fish or krill on the ocean's surface.

30 September: Stejneger’s Petrel

We saw several of these beautifully marked small petrels today. Stejneger’s Petrel breed on one island (Selkirk) in the Juan Fernadez Islands, off the coast of Chile. What are they doing up this way? Like many petrels (and shearwaters and storm petrels) these birds make an annual migration between breeding seasons. In the case of Stejneger’s, this is a 55,000 kilometre roughly triangular journey taking them as far as Japan and west of Hawaii, before heading back through the central Pacific (where we are), down towards Aoteraoa New Zealand before winging back across to Chilean waters and the next breeding season.

We saw several more of these migratory species during the day, all making their way south, mixed in with tropical breeders.

1 October: Pacific Golden Plover & Ruddy Turnstone

Waders/shorebirds vs Seabirds – Ever since leaving Pago Pago we have been visited by some interesting little birds which are not seabirds but are shorebirds or waders. These belong to a family of birds which number several long-distance migrants amongst them, moving from their breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra, Alaska or Siberia to winter foraging grounds in Oceania on islands such as Hawaii, American Samoa, Samoa and as are south Aotearoa New Zealand. They belong to a family of birds called Charadriidae.

Many of you on board will have heard the little tweet and thought it was the sonar, but if you looked around you might have seen a tiny golden coloured bird flying by. These are the Pacific golden plover, also known as Tuli in Samoa and Kōlea in Hawaii. They undertake some of the longest migrations of any birds from the Arctic tundra to Oceania, often non-stop. You will see them in parks and gardens busy foraging for insects and worms. Unlike seabirds they cannot feed on the ocean, they can only feed on land and many of the group are most at home foraging along the shore and in the intertidal zone, hence their common name of wader. Seabirds by contrast are most at home on the ocean where they find their food.

Yesterday we were also visited by another Arctic breeding wader, the ruddy turnstone. Even in its non-breeding plumage it is quite striking. This bird may fly as far as New Zealand. It took us by surprise as the tight little flock flew over the bow continuing on their journey. Waders can stop off on their migrations at islands and atolls to rest and feed before continuing to their favourite overwintering spot. Faithfully returning to the same location year after year.

2 October: Tropicbirds and flying manta rays

Many seabirds, while beautiful in their own right, do not have the spectacular or colourful plumage found in some land birds. There are exceptions and this trip we have two. These are tropicbirds, a group of three species, characterized by pairs of streaming central tail feathers, which may be as long as the bird's body. Sailors used to call them ‘marlinspikes’ and ‘bosun birds’. There are two species breeding in the Pacific – the white-tailed tropicbird and red-tailed tropicbird – and we have seen both on the trip so far.

White-tailed tropicbirds breed across Samoa, and the birds we saw early in the trip would have come from those islands. Many of them breed in forest, a long way inland, and at quite high altitudes. We see them at over 600m (1970ft) above sea level, near our home above Apia. And remarkably they nest in trees, often in holes in trees, and sharing the forest, with brown noddies and white terns which we have also seen on this trip.

Red-tailed tropicbirds nest on the ground, often under rocky overhangs, mostly on offshore islands. At the Kermadec Islands north of Aotearoa New Zealand, the subspecies there has plumage that is flushed salmon pink (roseotinctus).

Both species are solitary foragers, feeding well out over pelagic waters and often far from land. Their habit of flying above boats on the open ocean, like the boobies we’ve seen, may be a learned feeding strategy; flying fish are frequently flushed into flight by moving boats, providing plunge-diving tropicbirds increased foraging opportunities. They also take small, surface-dwelling pelagic fish and squid.

And our surrogate bird of the day? How about a flying manta ray seen this morning? No kidding, huge splashes when they land. And yep, we are logging all the surface marine fauna activity we see.

3 October 2024: Mottled Petrel- Homeward Bound

That’s if ‘home’ is an offshore island in southern Aotearoa, New Zealand, where (if you are a Mottled Petrel) you and your partner lay just one egg in a burrow dug in the ground in the forest. You both incubate it over 50 or so days, then raise the chick. After another 90 days or so the fledgling is ready to leave the nest. By then, both parents will likely have headed away on their annual migration, leaving the chick to follow alone.

Mottled Petrels, and yep we saw quite a few today, have a taste for the highly productive waters of the colder, higher latitudes in both hemispheres. During breeding, they venture deep into the Great Southern Ocean and have even been seen feeding amongst the pack ice north of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. In May, they head north, cross the equator, and spend their ‘winter’, the northern summer, in the North Pacific as far as the Bering Sea.

The Mottled Petrels we saw today are on their return journey, and we have obviously struck a popular route south, maybe even using the Howland and Baker and the Phoenix Islands as markers. They are about halfway home here. For many migrating seabirds oceans have no boundaries, one ocean.

Mottled petrels, like many petrels (and shearwaters and others of the family), are nocturnal when returning to land, coming and going from their burrows in the forest. Mottled Petrels share the forest on some of those southern New Zealand islands with one of the world’s rarest birds, the Kakapo, a large nocturnal flightless parrot.

4 October 2024: What do seabirds eat?

So, what do seabirds eat in an ocean that, at times, appears rather empty? There must be good food available to sustain the huge colonies of terns, noddies, boobies, and frigatebirds on a number of these atoll islands in Kiribati and the U.S. Pacific Remote Island Areas that straddle the equator.

That Wedge-tailed Shearwater hunts big fish? It's chasing the same prey that the fish are chasing. Tuna are near the top of the food chain in the open ocean: a predator of small and medium-sized fish that eats squid and crustaceans. Tuna, like many larger fish, force smaller prey close to the surface, where they feast, at the same time making that prey available to seabirds. These workups can make for spectacular feeding frenzies, and we saw a few of those as we approached Baker Island.

The other major prey item for many tropical seabirds are flying fish. Just think you have evolved an ability to fly to escape subsurface predators, like tuna, only to get picked off when you take to the wing. Dang!

5 October 2024: How do seabirds handle migration?

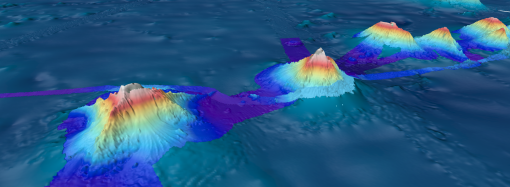

What a difference a day makes. We have been cruising these transects in the same general area for two days. We can see from the seabed mapping and the wonderful 3D modeling the submarine topography changes all the time. Topside, we were blown away by the sheer number of birds seen today, especially this morning. Short-tailed Shearwaters, like the Mottled Petrels that were such a feature yesterday, also like the colder climes and only transit through the tropics. This species breeds on offshore islands around Tasmania and the Bass Strait area of Australia and also ventures deep towards the South Polar Front when foraging.

We saw thousands of these birds pouring through in groups of up to fifty or more. They are also halfway on their journey back south, having pressed north, as far as the Bering Sea during their migration. In April, the year before last, we saw thousands of them heading north past New Caledonia, coming up through the Coral Sea after flying up the east coast of Australia. Free from breeding duties, they seemed ecstatic to be heading away for the southern winter.

These are birds made for speed - narrow wings, streamlined bodies, wee feet sticking out beyond their tails when they fly (a clue to their name). They are also extremely adept divers, able to dive 50m in search of prey such as krill, fish, and squid. Their beak is slender, with a hook at the end to assist in snatching their prey.

We are particularly interested in how well these migratory species fare when they spend these months on migration in the North Pacific. It is when they go through their annual molt, changing all their feathers progressively so they can continue foraging. It is also a period when they feed and get themselves in good body condition to meet the demands of parenting when they arrive back in Australia.

Sometimes, things can go wrong, such as the massive die-off of these shearwaters once they were back in Australia in 2023, an indication of something wrong in their Arctic foraging area that year. Let's hope they have fattened up nicely this year.

6 October 2024: When do seabirds sleep?

When do seabirds sleep? Well, the poop splatters on the Monkey and Forward Decks give a clue. We’ve had Red-footed and Masked Boobies hitching rides on the masts and upper superstructure some nights. Boobies, like a group of other seabirds (e.g., noddies, terns, tropicbirds, and some shearwaters), are visual feeders in the daytime. So, come night, they rest. If they are close to their colonies, they will return there and roost. However, over the open ocean, unless an obliging roost sails by (E/V Nautilus, for one), they sleep on the water. As seabirds, they are totally at home in the ocean.

Migrating shearwaters and petrels transiting through the tropics will also rest up. Especially when the wind speed drops. Flapping their wings is energy-sapping so they can wait out lulls until the wind picks up. Like yachts, they love a good breeze on which to sail.

That’s all fine if you can sit on the water, but there is one group of seabirds that cannot: Frigatebirds. There will be more on these birds later, but in terms of sleeping, and if you can’t chill out on the sea, what do you do? You sleep while flying! This study from the Galapagos shows that while sleeping mid-flight, frigatebirds don’t go completely on autopilot; the birds often sleep with only one side of their brain, leaving the other side awake.

8 October 2024: The eyesight of a Masked Booby

We often think of birds of prey like falcons and eagles as having exceptional eyesight. Boobies like this Masked Booby and their relatives, the gannets, have eyes that are angled forward and provide a wider field of binocular vision than in most other birds. They spy prey from a height, sometimes under the surface, and then plunge dive dramatically. On hitting the water, they are underwater for a short while, then bob up, with or without their prey.

However, seabirds’ vision is even more remarkable because they can see equally well above and below the water. While humans have to don a mask to create an air cell in front of our eyes, seabirds don’t need to. A study on gannets found that these birds can switch from well-focussed aerial to aquatic vision in less than 0.1 second — literally in the blink of an eye! These seabirds can change the shape of the lenses in their eyes. With the lens made more spherical when underwater, the light bends more, and a sharp image can be focused on the retina.

And it is not only boobies and gannets but other seabirds also, such as petrels and shearwaters, which are equally capable of making that shift. In Aotearoa, New Zealand, we ran a project examining petrels and shearwaters diving capabilities. What amazed us was their capability of seeing underwater.

9 October 2024: Bird Parasitism?!

There are many types of parasites, but out here on the ocean, we see a type of parasitism called Kleptoparasitism. This is really piracy, not parasitism, where one animal steals food from another. In the tropical ocean, frigatebirds rule. You will see them high up, often hanging above feeding groups of terns, boobies, noddies, and Wedge-tailed Shearwaters. They wait, watching, and when they spy a bird that has caught a fish, they will dive and pursue it with spectacular aerial acrobatics from both the hunter and the hunted. They will even tweak the other bird’s tail to force it to drop or regurgitate its prey, and if it does, it will swoop down and grab it often before it hits the ocean. True ocean pirates.

We’ve seen two species – the Great and Lesser Frigatebirds. And before you think too badly of these amazing creatures (remember they can sleep on the wing), most of the time, frigatebirds hunt their own seafood, flying fish as they skim the waves.

If there is ever a living bird that is closest to prehistoric pterodactyls, it would have to be frigatebirds. Like pterodactyls, they have huge wings, small bodies, and tiny legs and feet, ok for roosting and nesting in trees.

We have seen others from another group of aerial thieves on this expedition, the skuas. South Polar Skua (two) and a Pomarine Skua.

10 October 2024: Leach's Storm Petrel

We have seen flying fish every day and have discussed their being favourite prey for a number of seabirds in previous posts. But flying fish have to eat, so down the food chain we go. Flying fish feed on zooplankton and fish larvae. Not surprisingly there are a number of seabirds for whom zooplankton is their primary prey. This includes storm-petrels, the smallest seabirds we will encounter mid ocean. The smallest storm-petrel can weigh as little as 13g, the heaviest about 86g. In the context of the ocean these are really small birds, most will fit in the palm of your hand. But they are perfectly at home in the oceans, as their name implies, whatever the seas can throw at them.

We’ve only seen one species of storm-petrel on this expedition so far – Leach’s Storm-petrel. It breeds in the North Pacific, on islands off California all the way round to Hokkaido Japan and including some large colonies on the Aleutian Islands. They breed from April/May to September and then disperse, many heading south into the Central Pacific. The bird in the photograph is showing wear on the tips of its wing feathers, and it will soon undergo its moult, when it progressively replaces all its feathers before it returns to its colony to breed.

Storm-petrels belong to a group of seabirds known as ‘tubenoses’, which range in size from the really large albatrosses down to storm-petrels. Common to the group is that they have an amazing sense of smell, with storm-petrels the most acute. They use smell to detect potential food sources at sea and can do so from great distances. The name ‘tubenose’ comes from the arrangement of tube-like nostrils on their bills. To illustrate this here is a close up photo of storm-petrel we research back in Aotearoa New Zealand, the New Zealand Storm-petrel.

11 October 2024: The Sooty Tern

From 10nms adjacent to low-lying Baker Island, we could see the old beacon and the WW2 radio towers from a time when it was used as a refueling stop for US warplanes. It is nice to see land after five days of open ocean traveling from Pago Pago, American Samoa. But what was staggering was that at that short distance from the island, the sea below us was 5,000 meters deep. Such is the nature of many of these coral atolls and islands dotted across the tropical Pacific. Baker Island is a former atoll atop a seamount, one that pokes its head above the sea’s surface.

The island’s flat, desolate-looking surface is home to millions of seabirds. US Fish and Wildlife in 2007 recorded sooty terns (1.6 million), noddies, boobies, frigatebirds, and tropicbirds, and an earlier survey of the possibility of Wedge-tailed Shearwaters. After three days of open sea traveling, the numbers of seabirds encountered steadily increased, with frequent feeding and foraging aggregations of Sooty Terns, boobies, and attendant frigatebirds, while passing the adjacent Phoenix Islands and on our approach to Baker Island.

The rest of the science team aboard has been busy mapping seamounts north and west of Baker and Howland Islands. Seamounts are described as independent features of volcanic origin that rise at least 0.5 km above the seafloor, which, for the most part, in this region, is around -5000m. Those mapped are deep, with summits at around -3000m and -1000m. While it’s unclear how much influence these might have in terms of surface productivity, there is clearly sufficient to support the very large populations of seabirds on atolls and islands in this region. At home we have a great book in our library on seamounts.

12 October 2024: White Tern

Today, we saw quite a few foraging/feeding aggregations with White Terns, the dominant species, very strikingly bright white against sea, clouds, and clear sky. Sometimes with other terns, and Wedge-tailed and Tropical Shearwaters. This species really are truly pelagic in their foraging; the nearest land at midday was about 215nm east of Marakai Island, Kiribati, and we were 440nm west-northwest of Howland Island.

White terns construct no nest. Instead, it lays its single egg, often delicately balanced, on a branch, building, or rock. Newly hatched chicks have well-developed feet and claws with which they cling to their perilous nest sites. White terns haven’t been recorded on Howland and Baker Islands, but they have been recorded for several islands and atolls in Kiribati. In Hawai’i, White Terns are known as Manu-o-Kū, with a growing population within Honolulu, the busiest of Hawai’i’s urban landscapes. In Samoa, they are called Manusina and are a common sight flying inland over Apia, the capital city.

Another feature of the day has been the many smooth ocean surface slicks. These types of slicks have been well studied in coastal environments, for example, off Hawaii and California, where it is shown that they provide nursery habitat for diverse marine larvae. Whether that’s the case here in the open ocean, what we saw today with active fast-moving tuna schools, foraging and feeding flocks and terns, noddies, and shearwaters is certainly suggestive there is something out there!

13 October 2024: Red-footed Booby

Our day started off with entertainment plus. One of the two Red-footed Boobies that had hitched a ride overnight stayed on to give us a great display of ‘this is how to catch flying fish!’. After several miscues, he/she finally nailed it in spectacular style, much to the delight and shouts from the seabird team split between the fore and monkey decks. This bird was obviously good at pursuing flying fish, but it does beg the question of how young birds learn to catch their prey. A few days ago, we did see a pairing of an adult and juvenile Masked Boobies, with the adult taking the lead in most of the dives we saw. We know in Aotearoa, New Zealand, some terns are taught to catch prey by their parents.

But what of some of the migratory species – the petrels and shearwaters we’ve been seeing? Usually, the parents will cease visiting their single chick before it fledgests. So, when it comes to departing the colony, they will be well on their way to wherever their migratory path takes them. For those youngsters, they have never been to sea, the island and forest has been their home. But off they go. It’s tough that first year, and many don’t make it. But many do and return to their colonies, which is truly amazing.

Our route today took us north of the islands and atolls of Kiribati (the Gilbert Group) and south of the Marshall Islands, about 175nms between Mili Island (Marshalls) and Butaritari (Kiribati). Both groups run perpendicular to major current systems, the Equatorial Counter Current and the westward-flowing Equatorial Currents. Through the early afternoon we criss-crossed the boundaries between two of these currents; the water on one side smooth with few whitecaps, the other with a sea running as if we were crossing a shoal with wind-against-current kicking up a lot of whitecaps and standing waves. And not surprisingly, along this boundary was plenty of seabirds and fish school action, with numerous feeding aggregations.

14 October 2024: Bulwer’s Petrel

The modern distribution of seabirds across Oceania and the tropical Pacific is imperfectly known. There are numerous islands scattered throughout Oceania for which we know very little, or in some cases absolutely nothing, because of difficulty of access due to remoteness or natural barriers. Globally, seabirds are more threatened than any other comparable group of birds and their status has deteriorated faster over recent decades. In Oceania, the albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters, and storm-petrels (family Procellariidae - tubenoses), in particular, have lost more populations than any other bird family, mostly to predation from cats and rats.

Our bird of the day is Bulwer’s Petrel, a small all-dark petrel found in all three major oceans. It nests in crevices in rocks, in human-made or natural cavities, and even in the burrows of other birds. Mostly on small offshore or remote islands. We’ve seen a number this trip in the Baker/Howland/Phoenix area, but more commonly as we approached the Marshalls/Kiribati (Gilberts) and today as we press on towards the island of Kosrae in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). Today we have seen five. Some of the Bulwer’s Petrels would have been from the Phoenix Islands earlier in the trip. Others may have come down from Hawai’i (the largest colony is on Nihoa in the Hawaiian Chain) and/or Japan. Two of the birds clearly show moult, which generally follows breeding and may give us a clue as to which part of the Pacific they are coming from.

It is possible there are colonies of Bulwer’s Petrels yet to be discovered, and with eradication programmes recently completed or underway (e.g., Baker, Howland and Jarvis) this species and other petrels and shearwaters could recolonize them. Several species are known to occur in the Pacific and Oceania for which breeding sites are completely unknown and others for which breeding sites are suspected but not confirmed. Nothing like a challenge.

15 October 2024: Wedge-tailed Shearwater

If you have seen a large dark brown shearwater with a rather lazy flight moving across the waves and not appearing to be in any hurry, then it is undoubtedly a Wedge-tailed Shearwater.

It occurs in two plumage forms: dark-bellied and pale-bellied. They arewidely distributed throughout the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, where they breed on tropical and subtropical islands. Breeding is widespread on islands throughout the tropical Pacific, and as far north as the Hawaiian Islands and some offshore islands in Japan; south to the Kermadec Islands, New Zealand, and Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands, Australia. Breeding cycles are less strictly seasonal in equatorial birds than in birds at higher latitudes. We are likely seeing both trans-equatorial migrants as well as resident birds.

We are seeing Wedge-tailed Shearwaters most days. They have mostly been all-dark, with some a little smudgy around the face and underside, but not the full pale-bellied form so far. Shearwaters and petrels are not noted for beautiful calls. Wedge-tailed Shearwaters rarely call in flight, but regularly does so on ground or from within burrow, most frequently giving a

two-parted moan, likened to a child imitating a ghost, an "ooo-err". This call would definitely have resulted in fishers out around islands at night hearing ghosts or spirits.

SPREP is supporting work on this species in the Pacific. Wedge-tailed Shearwater chicks are harvested in remote communities in Vanuatu, and we are working with BirdLife International to support sustainable harvest regimes. Seabirds have been traditionally harvested across Oceania for thousands of years and in some countries, they remain an important cultural food source

and food security resource in difficult times such as when COVID hit. When communities had less access to outside resources. In addition, we are looking at plastics ingestion in this species and hope to establish a baseline for monitoring future changes in plastics ingestion and impacts.

16 October 2024: Black Noddy

We were a little surprised to see a solitary Black Noddy far from land today. They are a very abundant species across the tropical waters, and commonly seen close to islands, inside and outside of lagoon waters. When we do see them offshore, they are usually in groups, feeding flocks following and feeding in association with tuna. They are a stunning little bird, jet black with a white cap. Noddies are related to terns; we have seen two other noddy species on this trip: Brown and Grey Noddies. The name noddy comes from the male and female nodding their heads up and down with heads close together while courting.

They are a colonial breeder and commonly build their nests in trees (and shrubs). On some islands in the Pacific, they choose to nest in Pisonia trees which are found on islands that host large colonies of seabirds such as terns, noddies, boobies, or shearwaters. However! Pisonia trees produce extremely sticky seeds, and if breeding timing and seeds at their stickiest stage coincide, they can end up with seeds stuck to feathers and quite often unable to fly. Many years ago, in Fiji, we found one such unfortunate Black Noddy on a small island. We were able to remove the seeds, and release the rather untidy bird, a chance to survive.

Another Fijian island was ravaged by Cyclone Winston in 2016. Much of it had been covered in forest, which was the main nesting habitat for several species, including Black Noddies. The cyclone radically transformed it, stripping much of the vegetation, particularly the large trees. The Black Noddy population on the island plummeted, from more than 20,000 pairs to less than 1000 nests in 2021 (five years after the cyclone). The vegetation is returning, as are the bird populations.

17 October 2024: Brown Booby

When you have quiet periods spotting birds ahead and to the sides, there is always plenty of action from our hitchhikers on the forward mast as they chase their meals – flying fish. Red-footed and Masked Boobies have already made their appearance in these posts; now is the turn of the Brown Booby. Actually, this is just an excuse to include some neat diving shots!

During those periods of no sightings, you get to musing about things. For example, a booby dives, it plunges into the water to catch its prey, but how does it prevent water from being forced into the mouth, throat, and lungs at the same time as trying to catch the fish? Well, a study of gannets (close relation to boobies) shows that the bony structures that shape the sides of the beak where it meets the head create a slight opening between the top and bottom bill. The bird can then inhale and exhale through the sides of its mouth when it’s not diving. The main bone forming this structure, the jugal operculum, is not rigidly attached to the skull. As a result, when the bird hits the water's surface, the force of impact presses the bone against the top bill, like an automatic shut-off valve, temporarily closing the gap.

Today a huge squall swept through – heavy rain and wind – and took out most of the afternoon’s observations. Until then, it had been quite a Bulwer’s Petrel day.

18 October 2024: Kermadec Petrel

It's not the best of photos, but you do your best with birds at a distance and moving fast. But cool to be able to get a good ID on this one. It is a Kermadec Petrel, a species of the Southern Hemisphere’s subtropics, breeding on oceanic islands at around 30°S latitude right across the Pacific Ocean: from Lord Howe Island, Australia, all the way across to the Juan Fernandez Islands off Chile. This bird could be on its way south. A tracking study by Australian researchers on Phillip Island (Norfolk Island) shows they range as far north and west as Japan and the China Sea when not breeding.

It gets its name from the Kermadec Islands / Rangitāhua in northern Aotearoa, New Zealand. Specimens of this species were collected in 1854 at the Kermadecs and were sent to Europe to have it described for science. However, it wasn’t until 1863 before it was finally described – its scientific name is Pterodroma neglecta, i.e., ignored, overlooked, neglected, disregarded!

It makes its nests on top of the ground, not in trees, making it vulnerable to rat and cat predation. The second photo shows an adult on a nest last November – on a rat-free island!

19 October 2024: Let’s talk rubbish!

Until four days ago the amount of marine debris we’ve encountered could be counted on one hand – a couple of bottles here, a fishing float there, and a drifting bit of an old FAD. That changed dramatically with long drifts of rubbish; broken plastic stuff with cardboard boxes, plastic wrapping, cups, and bottles, plastic bags mixed with a lot of terrestrial stuff including coconuts. A lot of it looked like it had been in the sea long enough to collect algae. There was also an increasing amount of fisheries debris including buoys, ropes and netting. Note three fishing vessels were sighted yesterday – including a large purse seiner.

There are international rules governing discharges from vessels established under MARPOL (London Convention on Marine Pollution). However long line vessels have very little observer coverage so sadly there is no real monitoring of what goes over the side. We didn’t see any of the birds we’ve been seeing these last four days interacting with either the drifts of rubbish, or isolated items, which says something about the nature of their feeding – these birds prefer moving prey, like flying and subsurface fish. Other birds who are more opportunistic do mistake plastic for food and it has been found in many seabird species; in some cases causing malnourishment and death of chicks.

Some birds we have seen have been taking advantage of the larger items to use as roosts. We have also been seeing increasing numbers of logs, a couple large enough to let the bridge know. This suggests that the source of a lot of debris and logs could be large river systems in the Solomons, Papua New Guinea or further afield, rather the mostly atoll islands closest to us.

20 October 2024: Feathers for life

Seabirds replace all their feathers after they finish breeding. For non-breeders (those too young) it’s around the same time but starts earlier. This energetically demanding process of shedding and renewing their feathers typically occurs at sea, a period when birds need to take care of themselves. For those that migrate, such as some of the southern hemisphere breeders that we saw earlier in the trip, they undergo their moult (US spelling molt) once they get to where they will spend most of their time while on migration.

For some species of seabirds, moult can be quite dramatic. Penguins for example, undergo a catastrophic moult, shedding all their old feathers and replacing them all in one go. During that time, they are not waterproof and cannot go to sea, so must fast. For other seabirds, they still want to be able to fly and catch prey to eat so they go through a progressive moult. The Bulwer’s Petrel in this photo taken today shows how it is replacing its wing feathers from the inside (darker fresh looking feathers) to the outer most (the older brown feathers at the ends of the wings).

Looking after feathers is a vital performance for seabirds. A lot of care is taken using their bill to smooth out and align their feathers. We see it daily with our booby hitch hikers on the forward mast in between dives.

It’s a common myth that the waxy substance from a bird’s uropygial, or “preen”, gland is what makes feathers waterproof. This is not the case. While the waxy secretion is vital for the long-term health and maintenance of each feather, it is the remarkable physical structure of the feather itself that makes feathers waterproof. Each covert feather on a bird is structured so that, when all its parts are aligned and “zipped” together, it creates a mesh much like GORE-TEX™ with gaps too small for water with normal surface tension to penetrate.

21 October 2024: Streaked Shearwater

When you sign up for a voyage like this you have a few ‘be great to see birds’. Once we were north of Papua New Guinea and closing in on Palau we had been looking out for these birds. Chris has seen them off New Ireland, Papua New Guinea a few years ago, but it’s a first for Karen, who was really delighted. Well, we both were! Even at a distance. Now for birds closer in and better photos!

About ninety percent of Streaked Shearwaters global population breed in Japan, and the bird we saw today would either have finished breeding or was a non-breeder. Post-breeding their at-sea dispersal is fairly extensive. Most migrate south with large flocks occurring off the north coast of Papua New Guinea/West Papua. Some venture further south to Australia and even Aotearoa New Zealand. Click here for an extraordinary story about a Streaked Shearwater that took on a typhoon for an insane 700-mile sky-high ride of his life.

22 October 2024: Whale time!

Whales and dolphins belong to the group known as cetaceans divided into baleen whales and toothed whales which includes dolphins. This region is known to be home to a third of the world’s ninety species, but more may live here. They just haven’t been discovered.

All large whales were brought to the brink of extinction last century by whaling, but most species are now recovering. Over 36 million km2 of SPREP Member country EEZs are whale and dolphin sanctuaries or fully protect cetaceans. The whale we saw yesterday was likely a Sei Whale and is still considered Endangered by the IUCN. This whale belongs to the group of large baleen whales, so called for the sieve-like plates inside the mouth for sieving their prey, mainly planktonic crustaceans, and small fish. These great whales are highly migratory, spending their summers in Antarctica or the northern polar waters feeding in these highly productive waters before returning to the warm tropics or temperate latitudes to have their calves.

Another species we saw yesterday was the False Killer Whale or Pseudorca, essentially a large black dolphin with teeth whose favourite prey is tuna. This lively animal is considered Near Threatened and one of the key threats in this region is by-catch in tuna fisheries, by both long line vessels and purse seiners. SPREP is working to try to improve protection of these animals through the Western Central Pacific Tuna Commission and our Member nations.

We had seen melon-headed whales, and spinner and bottlenose dolphins earlier in the trip.

23 October 2024: Drinking seawater

Imagine sitting in a life raft, you have run out of fresh water (tongue hanging out), and no sign of rain. The seabirds are circling, keeping their distance … you ask yourself, what do they drink? Saltwater? You can’t!

Some birds do drink salt water, but not all. Many marine birds, such as penguins, gulls, terns, noddies, boobies, shearwaters, petrels (all those birds we have seen) have built-in water desalination filters. With salt glands and ducts connected to their bills that rid their bodies of excess salts, these birds can drink seawater straight up or eat prey, such as fish and squid, that are as salty as seawater.

All seabirds and many shorebirds have a pair of supraorbital (above the eye) glands that perform one of the kidney’s main functions: drawing salt ions out of the bloodstream. At the base of the salt gland, the ducts carry highly concentrated saltwater secretions into the bird’s nasal passages, where they drip out or are sneezed out of the body.

Today has been a mixed day – long quiet periods, then some busy ones with Streaked Shearwaters and a mix of dark and light-morph Wedge-tailed Shearwaters moving through. Dark morphs predominate in the South Pacific populations, and light morphs in the North Pacific.

Our bird of the day is a Common Tern, that snuck up on us, did a circuit then flew on. Common Terns breed in Asia, and North America. The region encompassing the Kuril Islands, Sakhalin, North Korea, and northeastern China is the most likely origin for the bird we saw.

24 October 2024: Tropical (Micronesian) Shearwater

Our last full day for this expedition. Despite head-on 20-30kns wind for some of the day we had a good roundup of birds. And one great surprise. We were keen to see the Tropical Shearwaters that breed in Palau and finally, after several long distance glimpses of small shearwaters hurtling along in the wind, we saw a number of them with a feeding group of Brown Noddies, White Terns and one White-tailed Tropicbird. Tropical Shearwaters breed across the Pacific with some researchers splitting them into three subspecies. We have the Polynesian subspecies breeding near our home in Samoa, in forested ravines. They also breed in American Samoa, and we had hoped to ‘bookend’ our trip with sightings of both subspecies. But no luck on the first two days after leaving Pago Pago.

Our bonus bird today was neither a seabird nor a shorebird! A White-throated Needletail, a largish swift did a wee circuit of the upper deck before heading on its journey to wherever. This quite extraordinary looking bird is a land or terrestrial bird species from the temperate and boreal forest zone between central Siberia and Japan. Despite it being out over the ocean, like most swifts, White-throated Needletails spend most of their lives airborne. They are long-distance migrants, most heading to Papua New Guinea and eastern Australia. They do venture as far south as Aotearoa New Zealand

It’s been quite a ride! It was a great trip, a great vessel, and a wonderful crew (fellow scientists and the crew themselves). Working alongside the mapping team has been a real eye-opener.

25 October 2024: Black-naped Tern

We were up at dawn for our arrival into Palau and to watch the pilot coming aboard (scaling the ladder up to the bridge deck). From a seabird perspective we saw a number of Tropical Shearwaters and plenty of Black Noddies outside the reef. With the pilot safely aboard and in charge negotiating the channel through to the Port of Koror, and despite the overcast conditions, enjoyed the sight of Palau’s forested limestone islands (the Rock Islands). Several flocks of terns and noddies feeding along the channel and roosting on markers. We docked around 9AM local time.

26 October 2024: Final round-up

The NA66 expedition passed through eight national EEZs: American Samoa, Samoa, Tokelau, Kiribati, USA (United States Minor Outlying Islands), Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. These are countries or territories with breeding seabirds, sometimes large seabird colonies numbering in the millions. To emphasize a theme running through this expedition, oceans have no boundaries, and we witnessed daily the passage of migrating seabirds from both hemispheres.

Observing feeding and foraging associations has been important, as experiencing active major ocean current boundaries. Other marine fauna recorded included: schools of tuna, many flying fish, dolphins and whales, a turtle, manta rays, and a black marlin. Being able to observe migrating shorebirds was an intriguing surprise. Seabird researchers work a lot with remote tracking technologies, however, a survey like this has the value of keeping us in touch, not only with the birds themselves, but their place in the Pacific.

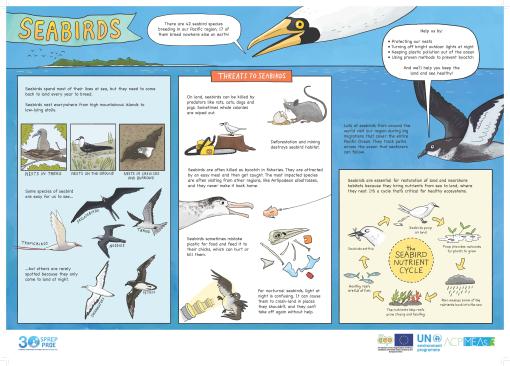

SPREP produced a set of educational posters in 2022 about the many threats facing our Pacific ecosystem and the species that live here, including seabirds.

In 2025 SPREP will also release the Pacific Seabird Survey and Monitoring Manual: Tools to Support Seabird Research across Ecosystems in Oceania. This will be launched at the inaugural Oceania Seabird Symposium, which will be held in Auckland, Aotearoa, New Zealand, in April 2025.

Seafloor Mapping Offshore Howland and Baker Islands

Howland and Baker Islands lie just north of the equator, about 1,800 miles southwest of Hawaiʻi. The islands are low-lying, sandy coral islands ringed by narrow fringing reefs and surrounded by the deep ocean. The US exclusive economic zone around Howland and Baker represents one of the least explored regions under US jurisdiction.