Revisiting a Whale Fall at Clayoquot Slope's Cold Seep

Exploring how deep-sea ecosystems function is one of the main goals of the whale fall work conducted at the Clayoquot Bullseye site near the Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) underwater cabled observatories, 1,250 meters deep at the Cascadia subduction zone. Scientists coiled the term whale fall to define the final resting place of a whale carcass after dying and sinking to the seafloor. Whale falls represent an oasis of food supply in an often food-poor deep-sea floor and sustain a diverse assemblage of marine organisms for up to decades.

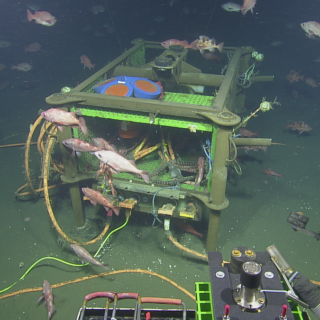

This whale fall was first discovered in 2009 by an expedition led by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. ONC began observing the site in 2012 during its yearly visits to maintain the observatory's seafloor instruments at Bullseye, where scientists are also interested in studying and monitoring the processes controlling methane gas seeping from the seafloor. They inspected the whale fall with ROV video surveys and sampling in 2012, 2020, and again during our current expedition to examine the rates of decomposition and degradation of the whale skeleton and to understand how the marine fauna associated with the whale remains have evolved since its first discovery.

The whale skeleton, which is approximately 16 meters long, is of an unknown whale species. Still, ONC Senior Scientist Fabio De Leo notes that this site is in a gray whale migration area, thus predicting a more significant probability this skeleton could be of a gray whale. The skeleton supports a rich benthic fauna (organisms that live near the seafloor), including many invertebrates and a few fish species, such as Cocculina craigsmithi (gastropod), Mitrella (Astyris) permodesta (bucinoid gastropod), Ilyarachna profunda (isopod), Paralomis multispina (crab), Coryphaenoides acrolepis (rattail fish), and Lamellibrachia cf. barhami (tube worms). These tube worms, likely the same individuals seen in 2009, are still making a home on the left jaw bone of the whale, which is remarkable.

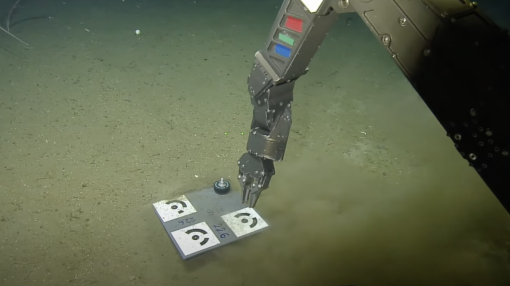

This year, the NA151 expedition repeated a photogrammetry survey performed in 2012 and 2020 to take high-resolution videos of the entire whale skeleton, allowing the estimation of whalebone decomposition over a decade. With onshore assistance from ONC Researcher in Residence Tom Kwasnitschka from GEOMAR in Germany, Fabio DeLeo led the dive, which performed the survey. The video was precisely calibrated for spatial accuracy by placing four marked checkerboards with signs resembling QR codes, with help from ROV Hercules' manipulator arms.

In addition to the survey, we took a series of sediment and water samples beside the whale fall and 10 meters away to analyze environmental DNA (or eDNA). This technique is becoming widespread for identifying levels of marine biodiversity present in a particular environment without the extraneous work of having to collect and sort through physical samples. Overall, after analysis by scientists at ONC and collaborators, the work conducted at the Bullseye site will provide a much better understanding of the fate of whale falls and their role in the nutrient cycle in deep ocean environments.

Ocean Networks Canada Maintenance and Exploration

For this expedition, we take a trip north to provide support to Ocean Networks Canada’s (ONC) wired seafloor observatory off the west coast of British Columbia where deployed technologies gather thousands of observations about dynamics across an entire tectonic plate.