Honors Research Program Brings High School Seniors to the High Seas

Written by: Ankush Joshi and Eric Lindheim-Marx

When we first stepped into the dorms at URI, we had absolutely no idea what to expect. For the first hour, awkwardness permeated the room like the Google Hangout conference we had done in the spring, in which nobody spoke unless spoken to.

Sam had promised us then that we would look upon this anxious time and laugh because of how comfortable we would get with each other by the end of the time in Rhode Island. At the end of our experience here in the Honors Research Program, in retrospect, Sam was absolutely correct. The numbers tell it best: pulling out a calculator reveals that we spent about 528 hours together in Rhode Island. We were already chatting like old pals by the end of the first week; by the end of the third week, we were a family.

The four boys selected for this year’s Honors Research Program were Michael Li, a student from Oxford Academy, Cypress, CA; Eric Lindheim-Marx, a student hailing from the Engineering Academy at Dos Pueblos High School in Goleta, CA; Ankush Joshi of the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, VA; and Noah Reardon, a student attending Lyons Township High School in La Grange, IL. Our interests and focuses are wide: Michael’s main interests are computer science and programming, Ankush’s is chemistry, Noah’s is robotics, and Eric’s are underwater archaeology and biology. Despite our varying interests, we were able to live, work, and have a great time together.

University of Rhode Island Component

At the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography (GSO) we had the privilege of interacting with researchers affiliated with the E/V Nautilus, GSO, and the greater scientific community. All interactions with scientists were full of invaluable information but a few inspired us and shed a new light on what it means to be a scientist. When we were not attending the lectures and informational meetings about the cruise, our attention was directing toward our main project: the surface drifters. A big challenge arose during the shopping run to get the supplies for building the drifter. Unintentionally, we had contacted the wrong Home Depot store to reserve our supplies, so when we arrived at the store, practically nothing on our shopping list was there! We had to come up with solutions quickly and on the fly. However, in this high-intensity hour, we were able to draw up another design, one that worked as well as our intended design.

Drifter Design

Our main goals in our drifter design were to increase durability, decrease windage, and create a design that would lend itself to promoting accurate transmission of ocean currents. We took a traditional Irina drifter design and created several modifications in order to make these goals a reality.

Durability. We constructed our mast from two square aluminum pipes, which together measured six feet. Aluminum was the perfect material in our eyes for three reasons: it is quite easy to work with, it is durable, and it is sleek, ensuring that we have minimal surface area and thus windage above the water. The sails, 22 by 40-inch rectangles, were prevented from sliding by being held in place by hose clamps on either side of the mast. Because the HRP program had sail material, having been graciously donated to us earlier, we had the advantage of using the more durable sail material over the more traditional canvas. To fasten them to the stakes, we folded two and a half inches of sail on the top and bottom sides over and epoxied it to the main body of the sail, forming a sleeve through which we could put the spars. We looped zip ties through all the grommets in a ring to make sure that the sails do not slide off the spars.

Buoyancy, Floatation, and Windage

Arguably the most important design modification that we made to our drifter was in floatation. Traditional Irina design drifters have a large buoy on the top of the mast for flotation. However, we decided to tether eight smaller crab pot buoys to the outer top corners of the sails, away from the center of gravity using fabric webbing tether. The tethering is important because it builds a considerable buffer zone if the drifter lists onto its side a little bit. With the tether buffer zone, a small list will not make the sail stick out of the water, but with no tethering, listing to one side could mean the sail sticking out of the water. This is not ideal because instead of collecting data on just currents, the data would be skewed thanks to the influence of the wind.

GPS Transmitter

Our last modification to the design was in waterproofing of the GPS. Obviously, since the GPS transmitter is an electronic device, water leakage would mean its demise. As we researched recent designs we found many with the transmitter encased in a heavy duty plastic box. We reverted to a more traditional approach and used saran wrap, a plastic bag, and tape. We spotted a few problems with the heavy duty plastic box. Most blatantly, a plastic box on top of the mast creates a lot of surface area above the water, and thus a lot of windage. Additionally, it was more expensive to buy a plastic box than to just use the plastic wrap and bag, which are materials that we had at hand. In order to test the GPS, we left the unit outside our dorm room for several hours and observed the fact that it was indeed pinging its location.

Finally, we boxed up our drifter so that we could easily transport it to E/V Nautilus, where we would reassemble it. Another advantage of our two pipe mast design was that the frame easily telescopes, making it compact in a relatively small box for the journey to Nautilus.

Michael’s Vector Field Program

Michael, the HRP student interested in computer science and programming, took upon the arduous task of creating a Google Earth vector field to help us better predict our drifter’s path. Using Java, he was able to create this vector field, which estimated the path of our drifter if deployed at our chosen site. The field is made up of arrows, which grow warmer in color and larger when the current is moving faster at a certain point and grow colder in color and smaller when the current is moving slower at that particular site.

At sea on E/V Nautilus

At sea on E/V Nautilus, we served as data loggers, standing watch around the clock and taking meticulous notes about the geological features and biological specimens observed on watch. In our spare hours, we also had to reassemble and deploy our drifters.

Reassembling our drifter was an important part of the agenda and we did so during the afternoon of August 9th. While the moderately rough seas added an element of difficulty to the re-assembly process, we were able to prepare the drifter in under half an hour. The compact design enabled us to secure the mast and sails with zipties, resulting in a sleek, yet strong, drifter ready to combat the waves and wind in a mission to catch the California current.

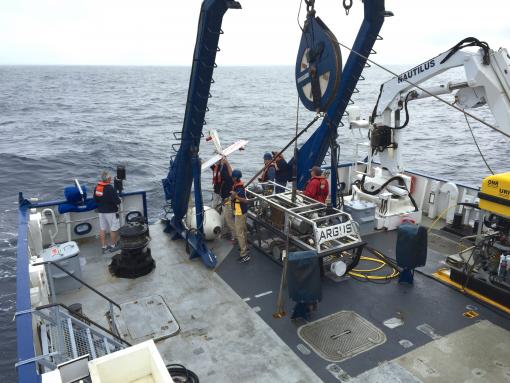

August 11th, the day of deployment, had arrived at last. In a final frenzy, we frantically added extra zip ties everywhere, providing double protection for our drifter. There was a grim silence as we fetched the drifter and brought it to the back deck of the ship. No one spoke as we walked slowly onto the back deck, vests on and hard hats strapped on tight. We formed a line around ROV Argus. Ankush passed the drifter to Eric, who passed the drifter on to Michael, who was standing at the edge of the back deck. Michael held it aloft for several seconds, waiting for the winds to die down. Finally, Noah got the all clear on the walkie-talkie to deploy the drifter. Battling the wind, Michael threw the drifter over the railing with all his might. We eagerly looked over the stern and looked down, only to see the drifter inauspiciously floating on its side. Hearts in our mouths, we all looked at each other, crushed. Then a shout came from Noah. “It’s correcting!” We whirled back and looked once more over the railing, and sure enough, the drifter was upright, bobbing away in the current. The relief we felt was indescribable.

Now that the drifter is deployed, its path can be followed at http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/drifter/drift_oet_2016_1.html along with the path of the HRP girls’ drifter.

Post-Deployment

Watching the map of our drifter, we were initially disappointed and a little worried about the drifter’s prospects. Immediately after deployment, it headed straight east, towards the beach. However, our worries turned into confusion when it made a full loop, and then our confusion turned into relief once the drifter finally started to head south. It headed south for a couple days or so, and then our worries resurfaced as it made an abrupt turn straight towards the Mexican mainland, Ensenada, Baja California. The drifter headed northwest for a few days, making strange arc-like patterns. All of us have been puzzling over what these arc-like patterns mean. Hopefully, since we are still in the range of Dr. Yi Chao’s CA-ROMS model, his company Remote Sensing Solutions can make sense of and use our data. Interestingly, the drifter has once again switched course and is now traveling south again, albeit closer to the mainland. In sum, although our drifter’s path has taken some worrying and confusing turns, we are happy with any data that we collect that can help Remote Sensing Solutions. So far, it has been 17 days since deployment, and our drifter is still going strong. May our drifter have a long life of data collecting ahead!

Final Thoughts

As a group, we have learned an incredible amount from this experience and we have made deep bonds that will remain strong for the rest of our lives. We have grown so much, and although we stepped onto the University of Rhode Island campus on July 9th as shy, nervous teenagers, we leave the E/V Nautilus having blossomed into mature, responsible young adults. One thing that will always stick in our mind is something that Sam told us reminded us nearly every day about our time as HRP students: you get out what you put in. We put in our all, and what we took away was an incredible experience that will stick with us forever.

Southern California Margin

In late summer, E/V Nautilus will be offshore Los Angeles to explore some of the most tectonically active (as well as densely populated) areas offshore California. The team will investigate the Southern California Margin, a broad area that fits entirely within the US Exclusive Economic Zone but that still remains largely unexplored.